Viscosity in fluid flow is similar to the concept of friction. If we want to keep a body at a constant velocity, we must have an external force to counteract the friction.

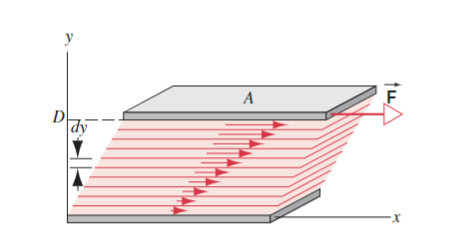

We can apply a similar logic to fluids by envisioning them as a series of plates.

In the example, a force

The speed of each layer differs by a

We know that the area of the top plate and each of the layers will have an effect on how much viscous drag there is, and thus the force

or, using

In the case for the rectangular layers above, the velocity gradient

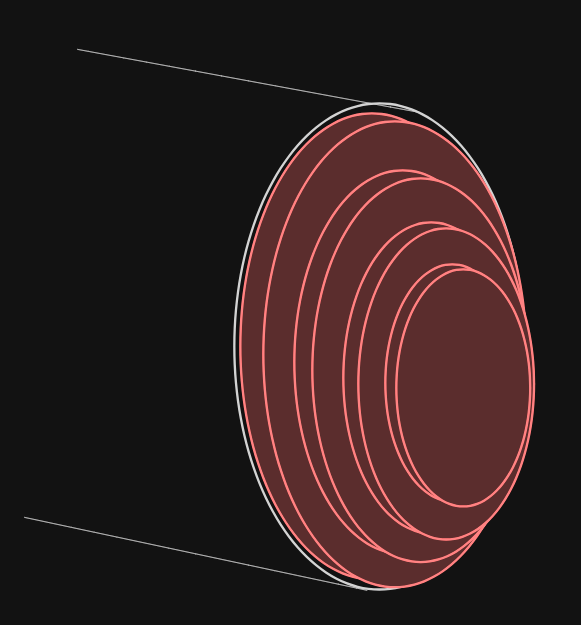

For a more practice example, we can look at viscosity in pipes.

In this case, our layers are not rectangular but cylindrical with varying radii. Assuming that the layer next to the walls is at rest, the speed in a shell of radius

Which depends on the pressure difference across the length of the pipe. The speed at the center of the pipe is:

Using more derivation, we can show that the total mass flux is:

This result is Poiseuille’s Law.