Transclude of Density

The Specific Gravity of a substance is defined as the ratio of the density of the substance to the density of the water.

Pressure is the perpendicular force per area.

A fluid exert pressure in every direction. For a fluid at rest, the fluid pressure acts perpendicular to any solid surface that it touches.

Let’s say we have a flat plane of some sort underwater. To find the force at a height

Applying that to the pressure equation,

We find that the area of the plane doesn’t matter in this situation. This is because underneath a liquid, increasing the area would mean increasing the amount of space available for the liquid to press down, so the ratio of force per area stays the same.

Pascal's Principle

Pascal’s Principles states that:

Pressure applied to an enclosed field is transmitted undiminished to every portion of the fluid and to the walls of the containing vessel.

If you increase the external pressure on a fluid at one location by

, this change in pressure is also experienced everywhere else in the fluid. All of hydraulics operate using Pascal’s principle. It lets us amplify small forces to move massive parts.

Proving Pascal’s Principle

We will prove Pascal’s principle for an uncompressible liquid.

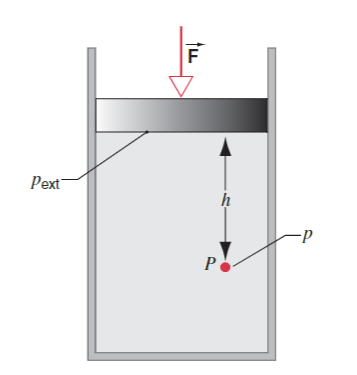

In this example, an external for

is applies to a cylinder with a piston, bringing about at to the liquid inside. We can write the pressure at a point a distance below the surface: if the external pressure is increased by

, then: Since the liquid is incompressible,

does not change: So, the change in pressure at any point in the fluid is equal to the change in external pressure, confirming Pascal’s principle.

Even though we have assumed that the liquid is incompressible in this case, Pascal’s principle is true for all fluids. For compressible fluids, a change in external pressure leads to a change in density, but the disturbance fades over time and the effect is the same.

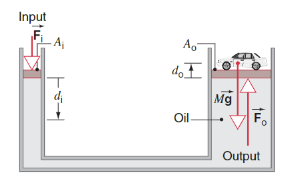

The Hydraulic Lever

The Hydraulic Lever is an application of pascal’s principle. In this example, an external force

is applied on a piston of area . On the other end, a car applies a force on a larger piston of area . In equilibrium, the two forces must be equal. The pressure on the fluid from the small piston is

, and according to Pascal’s Principle, this pressure is applied at every point in the fluid, including at the other fluid. As a result, the other fluid experiences an equal pressure, . Therefore: Since the ratio

is smaller than 1, is smaller than . When the car is lifted, the volume displaced by the movement of each liquid is the same (for an incompressible liquid). Since the ratio

is smaller than 1, similar to before, the distance moved by the large piston must be smaller than the distance moved by the small piston. Combining these equations: Link to original

Fluid flow can be either

- streamline (or laminar) — flow is smooth and regular

- turbulent flow — flow is not smooth and regular